Wildeor Voices

“We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain.”

Wildeor is an Old English word for “self-willed beasts” favored by Wildlands Network Founder Dave Foreman. It is a short-form expression for the concept that other species should be valued and protected for their own sake without regard to their usefulness or value to humans. To me, Aldo Leopold’s epiphany – that other creatures were more than just characters to be manipulated in humans’ stories – captures the sometimes hidden, but always beating, heart of Wildlands Network.

Wildlands Network’s founders spoke a lot to the intrinsic value of wildeors, particularly those with big teeth and claws. Wolves have always held iconic status at Wildlands Network. For instance, Dave Foreman, famous for his fiery speeches extolling the importance of the wild, would end each speech with a highly anticipated wolf howl, which the audience would enthusiastically join. Michael Soulé, regarded as the father of conservation biology and a primary Wildlands Network founder, always spoke of a continent-wide population of wolves as a key indicator of success in rewilding North America, while more colloquially exclaiming with a gleam in his eye, “I love wolves!”

Wildlands Network founders from left to right: David Johns, John Davis, Dave Foreman, Michael Soulé - Photo: Tracey Butcher

In Wildlands’ early days, we were spreading the word. Convening conservation groups working on the ground across North America and introducing to them not only philosophical thoughts of self-willed places and creatures, but also practical concepts of large-landscape ecology: cores, corridors, and carnivores. Restore, Reconnect, Rewild became our tagline. And, after about 20 years, these conservation concepts caught on and are now part of the broad conservation community lexicon.

When I came to Wildlands Network in 2013, we were doing our best to continue to communicate and unite the conservation community around the restore, reconnect, and rewild message. But we were struggling. The message had been heard in our conservation community, but frankly many didn’t know how to integrate it into their work, and some in the community had moved on, arguing that we needed to refocus on the “what’s in it for humans” case for wilderness and “open space.” Worse still, neither government policy nor on-the-ground activity was keeping up with the pace of species’ extinction and the fragmentation of habitat by natural resource extraction and human infrastructure. We had to shift.

For the past decade, Wildlands Network has taken a more pragmatic, grounded approach. While a love of wild places and beings is undoubtedly a primary motivator for our team, we have successfully focused our advocacy on federal and state policies promoting habitat connectivity and restoring connections through the funding of wildlife crossings and similar measures designed to stitch back together landscapes crisscrossed by highways and human infrastructure. Working at the federal, state, and local level, we have made the arguments that work. For instance, in advocating for wildlife crossings, we focus on how these structures protect human lives and property. We point out that over time they pay for themselves in terms of human lives saved and reduced health and property damages.

In the carnivore space, the animals themselves have done much of the heavy lifting by demonstrating their self-willed nature. Despite mostly adverse state agencies and rural populations, large carnivore populations are generally increasing, and they are on the move. Wolves are moving farther south in both Washington and California and recently showing up in New York State; a wolverine was spotted moving south from the Columbia River into Oregon; cougars are trying to move east. This is all bringing us closer to our vision of rewilded places (and the real test will be if they can be accepted at levels that will persist in these new locations).

Other interesting developments have occurred in the past decade that support a return to more wildeor-centric advocacy. Published, peer-reviewed science is documenting the social lives and structures of wildlife, and how our resource ownership approach to wildlife, particularly predators, disrupts these social structures. We are documenting, over and over again, what every pet owner intuitively knows – animals are prescient; they have emotional lives of their own, lives that we too often cut short with little regard. There has been a strong push for a more inclusive conservation community, with a particularly strong effort by the Biden Administration and non-profits to embrace indigenous communities, whose views towards the appropriate place of wildeors in nature differ from the Anglo-Saxon worldview.

Camera trap image from our red wolf project in North Carolina

Finally, there is a developing social consciousness that these animals with whom we share this place deserve to live their lives on their terms. Think about it: a single, solitary male cougar, who was just being a cougar, dispersing from a hostile territory in search of a safe space with a prey base and a female cougar, became a Hollywood star. P-22, who until earlier this year wandered the Hollywood Hills, and sometimes the Hollywood streets and backyards, became a celebrity. Adopted by the City of Los Angeles, P-22 was celebrated rather than feared. He had his own Twitter and Facebook accounts; Los Angelenos rooted for him to find a mate; forgave him when he was the leading suspect in the death of a Koala at the Zoo; and were thrilled when his image was discovered on their security cameras. What other animal has a memorial service with over a thousand attendees, and a Requiem published in the New Yorker after his death? More on that later.

I can’t argue with Wildlands’ pragmatic approach of the past decade; hell I started it. But I think it is time to talk more about wildeors in our advocacy work.

The concept of wild places and animals having intrinsic value to be protected and preserved is not one that everyone is ready and willing to embrace. It is a position that will meet fierce resistance from some circles because of the power that it holds. We know this to be true from lessons of our past when conspiracy theories rang forth that Wildlands Project was a UN-driven strategy to destroy private-property rights and to round up and force all humans to live in designated spaces while half of the Earth became a human no-go zone. This time around, it is likely to be categorized as yet another woke strategy to destroy the white Christian way of life. And it may get pushback from progressive circles who assert that wilderness and protected lands are constructs of the values of white elites that discriminate against other racial groups; arguments which fail entirely to “see” nonhumans.

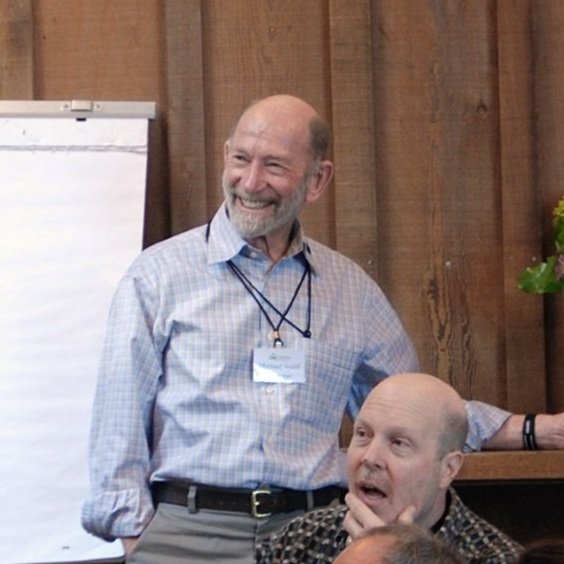

Michael Soulé with the author, Greg Costello - Photo: Tracey Butcher

But now is not the time to be timid; we must embrace the boldness of our founders. As Michael Soulé might say when reduced to his not-infrequent moments of teary-eyed dismay, we are losing the race against time and human selfishness. But Michael would then wipe his eyes and get on with it. And so should we.

In a series of essays to follow, dedicated to our greatly missed friends Michael Soulé, Dave Foreman, and Kim Crumbo, we will explore how we can increase the effectiveness of our advocacy by including arguments that recognize the intrinsic value of all living things.

“We patronize the animals for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they are more finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other Nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.”