State Wildlife Agencies Should Protect ALL Wildlife

There is an American revolution brewing among citizens across the nation. But no need for Paul Revere or muskets this time around; ours is a peaceful and growing social movement to rethink how we manage biodiversity in the U.S.

Having recently retired from my 35-year career as a scientist committed to wildlife conservation, I’m invested in current efforts to reform our state fish and wildlife agencies. I’m now a volunteer member of the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) Diversity Advisory Council, a 17-member committee that advises the department’s director on non-game wildlife. Given my observations, I believe WDFW faces challenges that illustrate why we need a national movement to transform our state wildlife agencies.

Wildlife management in this country depends on the combined actions of government agencies, non-profit conservation organizations, and individual citizens, with the legal authority to enforce environmental laws and wildlife protections resting in the hands of federal, state, and local governments. Over the past decades, the U.S. has implemented some of the world’s most comprehensive conservation legislation, yet 1 in 5 animal and plant species is at risk of extinction. We absolutely must do better.

The Focus on Hunters and Fishers

WDFW has a two-pronged mission: “To preserve, protect and perpetuate fish, wildlife and ecosystems while providing sustainable fish and wildlife recreational and commercial opportunities” (emphasis added). In other words, WDFW must work to ensure the conservation of all Washington’s fish and wildlife on the one hand, and provide for the recreational and consumptive use of the state’s wild resources on the other. This split personality often leads to conflict among the agency’s stakeholders and 1,800 employees, who together are responsible for meeting its very broad objectives with a $225 million annual budget—which has remained disconcertingly stagnant in recent years.

Dr. Fred Koontz surveys for martens in the Cascades. Photo: Amy Gulick

WDFW is funded through the state legislature and overseen by a 9-member Fish and Wildlife Commission appointed by the governor. The struggle to set WDFW’s priorities is especially troublesome when these priorities become politicized by certain interest groups who feel they have a preferential stake in the department.

Hunters and fishers (“consumptive users”) possess a strong sense of entitlement in Washington as they do countrywide, mostly because state wildlife agencies have historically relied heavily upon these groups for funding through licenses, permits, and federal excise taxes on guns, ammunition, and fishing and boating equipment. But there are problems with this legacy of financial dependence—chief among them that hunters are in decline and angler numbers are flat.

Today, Washington’s hunters comprise less than 4% of the population, and fishers only 10%, yet they together supply about 35% of WDFW’s revenue. Nationally, the funding discrepancy between consumptive and “non-consumptive wildlife users”—bird watchers, campers, hikers, and other outdoor recreationists—appears even more dramatic, with reports suggesting that hunters and anglers in some states account for 60%–90% of wildlife agency revenues. There is more to the story, however.

Based upon my back-of-napkin calculations, the average Washington hunter pays WDFW about $150 annually from licenses, permits, and taxes, and fishers pay $75. In contrast, each non-consumptive wildlife user provides WDFW with $5–$10 each year through taxes. But because there are many more non-consumptive users than hunters and fishers, this group covers roughly 35% of WDFW’s budget as well, with federal funds and other revenue sources making up the remaining 30%. Additionally, it is important to note that state wildlife agencies are only one component of the wildlife and habitat conservation ecosystem in the U.S, with the non-hunting public paying about 94% of the total tab.

Non-consumptive wildlife users, like these wolf-watchers at Yellowstone National Park, contribute significantly to wildlife conservation. Photo: Robert Long

Regardless of the budgetary numbers (and it is easy to quibble about the exact calculations), most WDFW staff treat hunters and fishers as their primary customers, and hunting and fishing as their main business. This is not a surprise. Consumptive users buy licenses, vigorously discuss and debate management regulations with staff, and actively lobby the governor and budget-setting legislators.

On the flip side, I have observed that wildlife enthusiasts in Washington are largely unaware of their tax contributions to WDFW and the department’s role in non-game conservation. Thus, when non-consumptive users advocate for increasing expenditures for non-game or endangered species conservation—which currently account for less than 5% of WDFW’s budget—they have relatively little political clout.

Stuck in a Rut

As I learned more about agency dynamics as a WDFW volunteer, I began to ask myself, “Why is there a continued emphasis by state wildlife agencies on hunting and fishing when we are facing a growing list of human-caused threats to all wildlife?” Remembering that mothers know best, I recalled that my own mom, a passionate history teacher, taught her students that to understand the present, first examine the past. Once this historical trajectory is understood, a future course can be better envisioned.

The history of wildlife management in the U.S. has been one of evolving values and associated human behaviors, shaped by changing ecological conditions, greater science-based knowledge, and effective political persuasion. While Native Americans and Europeans living in this part of North America between the 14th and the early 19th centuries made some attempts at wildlife protection through agreed upon social norms and laws, early settlers’ primary relationship with wildlife before the mid-19th century followed a consistent pattern of exploitation moderated by very limited and utilitarian efforts to sustain certain wildlife populations.

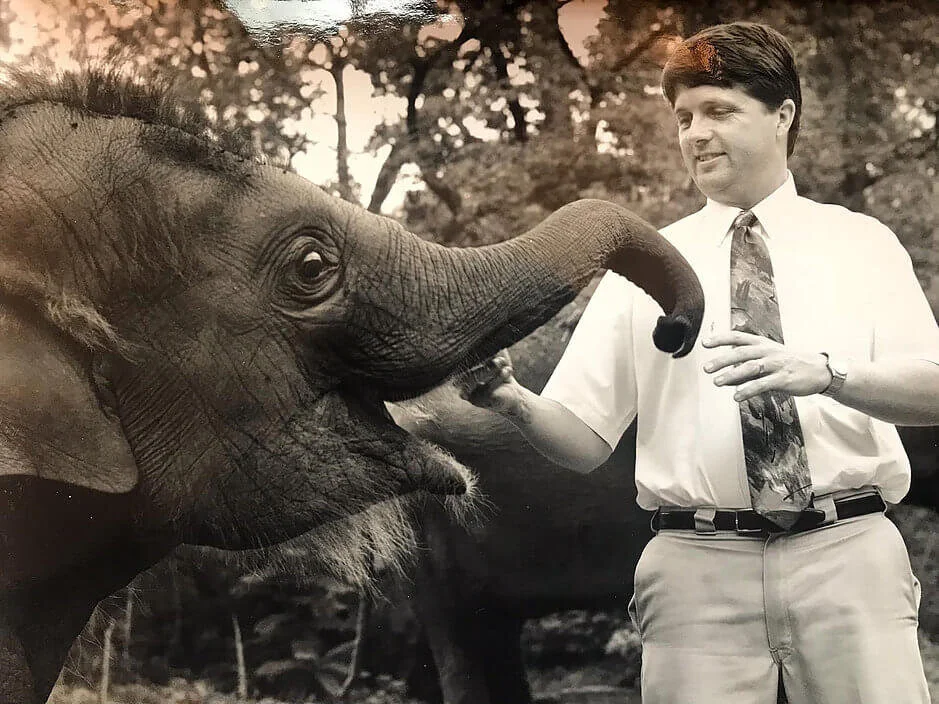

Dr. Koontz feeds a young elephant during his early zoo days. Photo: Fred Koontz

By 1870, Western expansion and population growth had fueled an expanding meat market and the overhunting of game animals, with severe population declines of bison, deer, and waterfowl. This alarming trend sparked the modern conservation movement, which has grown into what wildlife professionals today call the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The movement was primed by 3 influential precedents:

the writings of popular naturalists like Emerson and Thoreau;

the 1842 U.S. Supreme Court case Martin v. Waddell, which codified the concept of wildlife as “public trust” and places much of the responsibility of wildlife stewardship on state governments; and

the development of a strong sport hunting constituency.

The 6 decades between 1870 to 1930 were pivotal to wildlife conservation because of the creation of conservation-related infrastructure, including state fish and wildlife agencies, numerous sportsman clubs, conservation and scientific organizations, Yellowstone as the world’s first national park, the U.S. Forest Service, and our first national legislation for wildlife conservation—the Lacey Act.

President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), an avid big game hunter, argued that hunting, public lands, and wildlife conservation were mutually supportive. When Franklin Roosevelt became president in 1933, conservation was boosted among the working class by the hiring of 3 million unemployed workers to build 800 new parks, plant 2 billion trees, and carry out other environmental initiatives. And in the 1930s, several important government research programs, such as the Cooperative Wildlife Research Program and the American Wildlife Institute, improved training for wildlife biologists and elevated the importance of science in wildlife policy.

As the conservation ecosystem grew, so did questions of purpose and funding. Was the aim to “conserve” natural resources for human use or to “preserve” nature as an end in itself? (Consider the different values underlying logging in our national forests versus the aesthetic enjoyment of our national parks.) The Pitman-Robertson Act of 1937 firmly set the tone of consumptive use in our state wildlife agencies. This act created an 11% federal tax on guns and ammunition to be distributed to states based on the number of hunting licenses sold, birthing the mantra that “hunters pay for state wildlife agencies.” Similar taxes on consumptive use were put in place at the federal level, such as duck hunting (Duck Stamps) and fishing (Dingell-Johnson Act).

Duck Stamp Contest in Washington D.C., 1951. Photo: USFWS

State wildlife agencies were entrenched as “fish and game” departments by 1970, managing for the sustained take of game animals and fish. Then came the era of Earth Day (launched April 22, 1970) and the public’s demand for stronger environmental laws, including the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA). Many states developed state-equivalents of ESA laws and non-game programs to list, recover, and protect endangered animals—often in collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (Washington’s non-game unit was operational by 1978.) Regrettably, as the responsibilities of state wildlife agencies multiplied with time and funds became tight, the questions of purpose and funding re-emerged.

In recent decades, the federal government has increased funding to states for biodiversity conservation. For example, since 2005, it has provided funding to all 50 states for State Wildlife Action Plans—comprehensive blueprints for conserving fish, wildlife, and natural habitats. But in general, federal funds for wildlife diversity has been inadequate, and typically require matching grants from the states. Meanwhile, states are faced with either finding new sources of revenue for managing non-game species or cutting traditional programs for consumptive users.

I hope this history lesson helps to unveil the main reason behind the conflict between traditional consumptive users of game animals and fish, and those advocating for greater agency emphasis on preserving all species. Over the last 50 years, many new policy directives to study, recover, and protect threatened wildlife have been added to the workload of state wildlife agencies, but these directives have not been accompanied by necessary changes in the user-pays funding model or in an agency culture dominated by hunting and fishing. Despite much hard work and some significant successes achieved by the relatively few agency staff assigned to non-game efforts, we are stuck in a deep and deeply harmful rut—and wildlife is paying the price.

Breaking Free

State wildlife agencies need to forge a new path by modernizing their mission focus, relevancy, and funding based on the world we live in now. I am obviously not the first to say this. For more than 3 decades, many biologists and conservation groups have vocalized similar opinions, usually coupled with seeking more funds for state agencies to work on endangered, non-game animals and fish.

For example, the recently created Alliance for Fish and Wildlife is lobbying for the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act (H.R. 4647). This bill, introduced by Representatives Debbie Dingell (D-Michigan) and Jeff Fortenberry (R-Nebraska) in late 2017, would provide $1.3 billion in annual funding to state fish and wildlife agencies. The money would go toward conserving state-identified at-risk species, with $7 billion to $12 billion in funding generated by oil, gas, and onshore mineral royalties. WDFW would receive about $25 million each year—more than 5 times what it now spends on at-risk species.

The sharp historical focus on recovering overhunted game made sense at the turn of the 20th century, when people had no awareness of the impending extinction crisis nor a detailed understanding of how biodiversity is essential to human wellbeing. And this targeted focus on managing game and fish generally succeeded. Most game and fish populations are in relatively good health today, and the user-pays model was sufficient for many years. But state wildlife agencies are now in serious financial decline because hunter and angler numbers are down, resulting in less license and tax revenue. What worked well for wildlife agencies in the first half of the 20th century won’t necessarily work well today. Conditions change.

My experience at WDFW suggests that mission focus and relevancy are equally important to funding when it comes to advancing conservation. Before we seek more funding for our state agencies, we should make sure we and they are asking some key questions, like: Why is it important to conserve wildlife today? Why dedicate more valuable public funds to saving wildlife? Should wildlife funding come from the federal government or state governments? What is the appropriate amount of funding for wildlife conservation? Who stands to benefit most from these funds?

A wolverine visits a camera-trap station in the North Cascades of Washington. Wildlife agencies should place greater emphasis on research, monitoring, and program evaluation for species of conservation concern. Photo: Woodland Park Zoo

From a human-centric perspective, my answer is that we must protect the full range of benefits wild animals provide to people, including ecological benefits, sustainable use, and aesthetic value. I and many others would add that animals have intrinsic value that alone warrants our compassion and care. Put another way, the first part of WDFW’s mission, to preserve, protect and perpetuate fish, wildlife and ecosystems, must be given higher priority in response to our current ecological and environmental conditions.

Among other changes, agencies must place greater emphasis on research, monitoring, and program evaluation—in short, science-informed management. With this said, focusing more broadly on the full diversity of wildlife does not mean that WDFW ought to abandon or even diminish its role in managing hunters and fishers.

Once the “why” of protecting wildlife equates to ensuring human health and wellbeing, the importance of WDFW’s mission will be elevated and changed. WDFW’s work is not just nice to do for recreational purposes and some commercial interests, it is essential for our children’s future.

With new vision, WDFW’s focus could and should expand to include a larger array of species, and should among other things place greater emphasis on habitat restoration, wildlife corridors, and protecting ecosystem diversity. Furthermore, the historical split between consumptive users and non-consumptive users, and arguments about who is paying for WDFW’s services, becomes a false dichotomy. Everyone has a stake in WDFW’s preserving the full range of Washington’s wildlife as part of creating a sustainable world.

Significantly, with a paradigm change that links wildlife preservation to the quality of life for all, we should be able to more easily argue for new revenue sources from general tax funds and to rely less on hunting and fishing revenues. In Washington, for instance, we could follow Missouri’s lead and enhance wildlife conservation funding with a 1/10 of 1% addition to the state sales tax, which would provide another $150 million of revenue. I can think of no more worthwhile a cause.

Take Action

Revolutions are not easy. Join us in changing the role of your state wildlife agency by taking these steps:

Think about how much are you willing to pay to strengthen wildlife conservation in your state. Do you know how much you are paying now?

Learn all you can about your state agency by visiting its website, signing up for newsletters, commenting on public documents, and attending meetings of oversight boards or commissions. What programs and commitments are dedicated to threatened and at-risk species?

Become familiar with the proposed Recovering America’s Wildlife Act. Contact your national legislators and let them know you support increased funds for state-designated at-risk species.

Consider volunteering for your state wildlife agency. There are usually a variety of opportunities, including a growing number of fascinating citizen science projects.

Dr. Koontz’s career as a conservation biologist included positions with the Wildlife Conservation Society, Wildlife Trust, and Woodland Park Zoo. He also served as an adjunct professor at Columbia University and University of Washington. His wildlife projects took him around the globe, and included work on behalf of howler monkeys and manatees in Belize, forest elephants in Cameroon, tigers in Malaysia, and snow leopards in Kyrgyzstan. Dr. Koontz currently serves as an advisor for Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.