New Report Highlights the Evolution and Drivers of State Habitat Connectivity Policy in the United States

Legislation has focused on wildlife crossing prioritization, identification, and crossing funding. Photo by Adobe Stock.

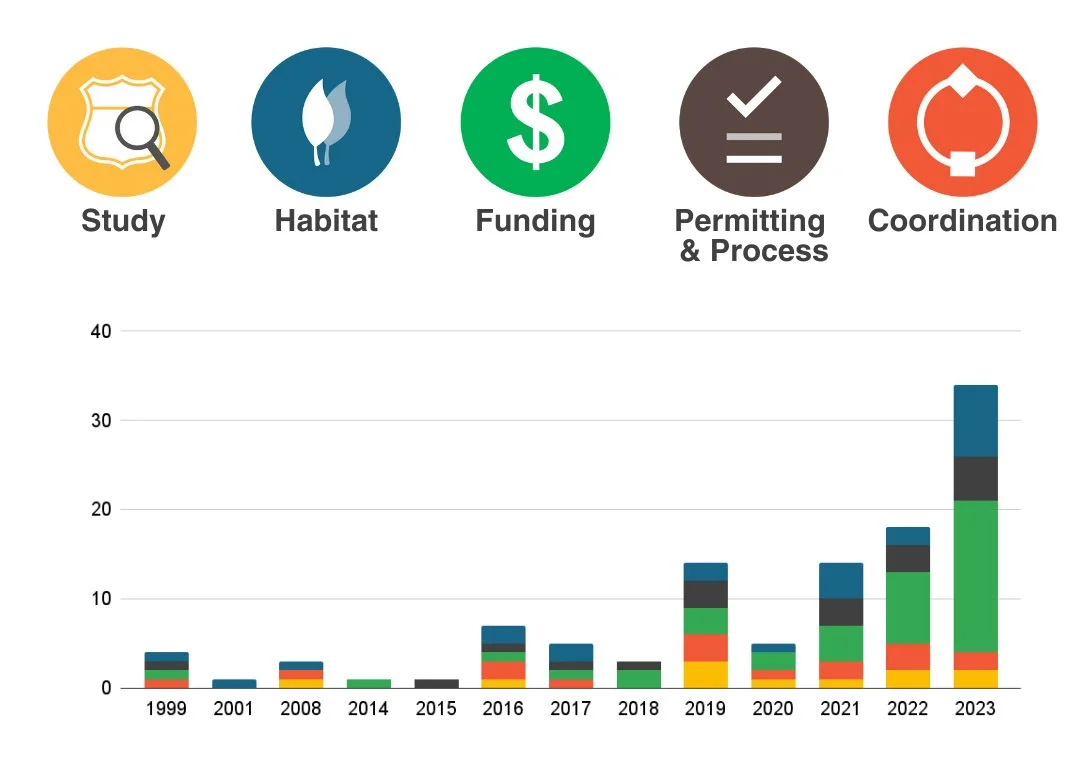

80% of all U.S. habitat connectivity legislation has been passed since 2019, successfully connecting vast landscapes and improving roadway safety for both humans and wildlife. Connectivity policy specialists Erin Sito, U.S. Policy Director at Wildlands Network, and Logan Christian, Wildlife and Habitat Coordinator at the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators, have analyzed this growing trend in legislation and have detailed their findings in a new, comprehensive report titled: “State of the States: A look at how far U.S. state habitat connectivity legislation has advanced and what is working.”

The two organizations hope that the guide can help future state policy efforts by presenting diverse approaches to legislatively advancing habitat connectivity conservation, as the report shows what has worked to date by providing case studies on several states that have passed and are implementing their legislation.

Additionally, the research conducted for this report shows that related federal legislation has had a tremendous catalyzing effect on state action in the past few years. As a result, the authors hope this report also provides information to federal decision-makers interested in learning more about how Congressional investments impact state success.

To learn more about how this report was created and how you can approach a state habitat connectivity policy analysis in your state, you can reach out to Erin and Logan, read the report, or begin with a primer on the key takeaways below.

Audio: Listen to the key points discussed by Erin Sito and Logan Christian in their interview.

What important habitat connectivity policy insights does this report identify?

Erin: To start, this report identifies the key catalysts that have driven state habitat connectivity legislation over the past 25 years. Outside of Florida, California, and a few other states that got started on habitat connectivity policy early, national-scale growth in state legislation began around 2018.

Two things happened: 1) In early 2018, Secretary of the Interior Zinke signed Secretarial Order 3362 during the Trump administration, which encouraged states in the West to preserve big-game habitats. Many Western states took note of this new federal support and provided directives and support to their agencies to study big game movement and create action plans for migration corridor conservation.

And 2) In July of 2018, Wildlands Network presented at the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators (NCEL) Forum on how legislators from around the country could pass legislation to conserve wildlife corridors and build wildlife crossings in their states. At this forum, Wildlands Network had provided model wildlife corridor legislation for consideration, which directed state departments of transportation to work with their wildlife agencies to map corridors, propose needed crossing locations, and create an action plan to conserve corridors and build crossings.

After that, we saw a huge spike in connectivity policy both introduced and passed in 2019.

Several years later, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law of 2021 became another significant catalyst. This legislation created a new, federal, discretionary grant program and made $350 million in dedicated funding available for projects that would reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions and improve habitat connectivity. The creation of the first-of-its-kind Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program led to another huge spike in wildlife crossing funding and prioritization legislation in 2022 and 2023, as the federal program requires state applicants to provide matching dollars for their proposed projects.

Logan: One of the other big trends we found in the report is that there's a lot of replication happening across states. Through our analysis we identified five categories of habitat connectivity legislation: studies, coordination, funding, permitting and process, and habitat. Many states are taking similar approaches within each of these categories. For example, of the states that have passed legislation for “studies”, most are both studying where wildlife corridors exist and where the highest-priority wildlife crossing sites should be located.

In other words, legislators are realizing that they don't have to reinvent the wheel: there’s bill language, proven methodologies for transportation departments and wildlife agencies to coordinate, and funding mechanisms that they can build on directly from this report.

That said, it is clear that states are now taking these successful policies and molding them to fit the needs of their state.

There are so many different geographies, species, and landscapes in every single state, so states need to tailor these legislation models to their specific wildlife, habitat, and infrastructure needs.

States in the West have tended to focus on big-game migration with the volume of undeveloped land in the West, especially in the wake of Secretarial Order 3362. While white-tailed deer-vehicle collisions are certainly an issue midwestern and eastern states are grappling with, these states have also provided passage for non-ungulate species, like black bears, bobcats, and Florida panthers. Some eastern states, like New Jersey, are also thinking about the less high-profile species, especially endangered species.

How can readers benefit from using this report?

Erin: If your state hasn't adopted habitat connectivity policies yet, you can use this report to see what other states have already done, whether that's passing legislation, handing down an executive order, or creating a memorandum of understanding between agencies.

If your state has passed connectivity legislation, you can use this report to see how others are doing with their implementation; What are some of their successes? What are some of their roadblocks? We are hoping that states can learn from others and adjust accordingly for their own connectivity policy approach.

What message would you hope decision makers take away from this report?

Logan: This is one of the most bipartisan environmental issues that you can take on as a state. The fact that both California and Florida have been leaders on habitat connectivity legislation demonstrates that this issue transcends political differences. Most of the bills that are being introduced have bipartisan support. There's recognition that this issue doesn't have a political bend – it's really about protecting human safety, saving money in the long run, and creating more space for wildlife in our ever-changing world.

Erin: In a lot of states, legislation has focused on wildlife crossing prioritization, identification, and crossing funding, but not necessarily on habitat conservation within crucial habitat cores and corridors that necessitate the need for a crossing to begin with. While crossing legislation is an incredible step, one thing that I don't want to be forgotten is that the wildlife corridor as a whole matters too. We have to think beyond roads – we have to think about the large landscapes that we're trying to connect with these wildlife crossings, because, for them to be useful, land must be conserved on either side of the road and then connected to adjacent lands and habitats.

Florida is an example of a huge success model for conserving a large, defined corridor. Virginia has also taken the approach of both conserving corridors and prioritizing crossings simultaneously with their Wildlife Corridor Action Plan.

What will policy look like in the coming years?

Logan: That's a great question. Most states lack a mechanism for permanent, ongoing funding. In the 2024 legislative session, Utah was one of the first states to create year-over-year, dedicated funding for crossings, Florida is consistently appropriating hundreds of millions of dollars to protect a wildlife corridor, and Wyoming has tapped an existing permanent trust fund to support habitat connectivity projects. However, outside of these examples, there hasn't been much work to establish permanent funding. It’s a gap that states will likely start addressing in order to take advantage of existing funding sources from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Erin: I think we’ll also see legislation in the coming years focused on infrastructure outside of roads. For example, virtual fencing and wildlife-friendly fencing bills. We saw one pass in New Jersey this year, and other states like Oregon have attempted similar legislation.

Another theme is wildlife connectivity and development. We have seen bills that require the incorporation of habitat considerations in zoning decisions and when citing renewable energy projects or housing developments to reduce the impact on wildlife movement across the landscape. Bills in California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, and Virginia are beginning to address these other types of infrastructure.

Any last thoughts on the report?

Logan: It's never too late to get started. Some states are behind the curve, but there is still a unique opportunity to take action with all of the federal funding available that hasn’t existed before. The Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program and other wildlife infrastructure funding opportunities will be available for at least another three years.

Erin: If you take anything away from the report, I hope that folks can see that when states buy into conserving habitat connectivity and the federal government reciprocates by providing funding and other technical support, we see a lot of growth and amazing action on the ground to connect and restore habitat for wildlife.